Home

Donate

Personal

Biography

Jobs / Green New Deal

Global Warming

TPP

Health Care

Palestine, Israel

Syria, Iraq, ISIS

Immigration

Social Security

The Other Candidates

News and Links

FAQs

Schedule

Green Party 10 Key Values

Anti-Racism

Anti-War

Economic Development

in Charlevoix

Summary

of 2016

Congress

Campaign

Summary

of 2014

Congress

Campaign

Summary

of 2012

Congress

Campaign

Summary

of 2010

Congress

Campaign

Summary

of 2008

Regent

Campaign

Diary

of 2005-06

Commissioner

Campaign

Summary

of 2004

Prosecutor

Campaign

|

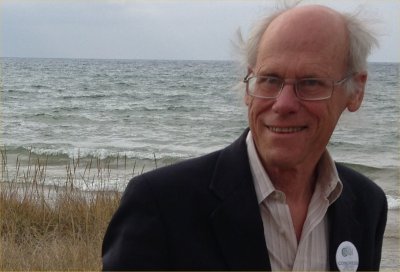

Ellis Boal grew up in Winnetka, Illinois, spending summers in Charlevoix. He worked on the family sheep farm there, stacking hay and cleaning the barn.

He attended Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, excelling academically and athletically. He graduated in 1966, cum laude with high honors, ΦBK. After hitch-hiking around Europe he started graduate school in the math department of the University of Chicago on a multi-year NSF fellowship, and left after a year.

He did odd jobs for awhile, including a stint in 1967-68 teaching math at Crane Technical High School on Chicago's west side. Rioting broke out in the school the morning after the assassination of Martin Luther King. The situation for white teachers was quite tense, but he was able to get out a side-door and make it home. A few teachers did not return to work when school resumed. He did and served out the year.

(King observed a month before his death, "a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear? ... It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met.")

Boal wasn't a good teacher. In 1969 he started law school at the University of Michigan. He was active in a variety of student activities, particularly the 1970 B.A.M. strike, one of the most successful in campus history. Over three hundred professors and teaching assistants cancelled classes and many departments were shut down. After eight days, the regents gave approval to the essential demands of increased minority aid, services, and staff, and agreed to work toward a goal of 10% African-American enrollment by 1973.

Disillusioned with an elite, suburban school, Boal left Michigan after a year, migrating to Detroit with 35 of the student SDS chapter to become revolutionary working-class organizers. Leaving the group within months, he continued to share its goals. He returned to law school at Wayne State in Detroit, changing his intended interest from criminal law to labor law. Wayne accepted his Michigan credits, and he graduated in December 1972.

After working for a short time with a firm, he had a solo practice in the city for 26 years, specializing in labor, particularly in dissident labor in the UAW and Teamsters unions.

|

|

The Uhrick Red Sox, 1957 Charlevoix Summer Softball Peanut League Champions. Front row: Larry Struthers, Ellis (Teddy) Boal, Jerry Drost, Louie Poole, John Toumela, Billy Marme, Billy Fowle, Larry Marme. Back row: Herb Cumings, John Flynn, Coach Bill Marme.

|

In 2000 he semi-retired and moved to Charlevoix, near his parents. Boal's grandfather first bought land there in 1912. Boal and his father both grew up there in the summers.

Boal's career highlights include:

Admissions to federal courts of appeal in Cincinnati, Boston, Chicago, and Washington DC, the US Supreme Court, and the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians Tribal Court. Counsel of record in cases arising in Michigan, Ohio, Nevada, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Illinois, North Carolina, and Puerto Rico. Listing in Who's Who in America, 2008. Membership on the steering committee of This Is Our Town, the citizens group formed to stop Wal-Mart from coming to Charlevoix Township. Wal-Mart is the biggest company in the world. In many small ways, working with many other people, Boal contributed diligently to the effort. The company was forced to gerrymander its own plan, and then threw in the towel in 2004. As Boal later wrote to the Charlevoix Courier and Petoskey News-Review, the people won because everyone in town -- with all their different interests -- kept their eye on the ball. The ball was Wal-Mart. The story is an object-lesson of how county government working together should be run. Later Charlevoix Township voters approved a zoning amendment by 61%, for which Boal and other TIOT members lobbied, which will keep big box Wal-Mart-type stores out of the township forever. Boal co-chaired the Up North Green Party in 2000-06. In 2000 voters elected Green candidate Joanne Beemon as drain commissioner, but other local officials impeded her duties. The drain code required that Beemon serve office hours of at least eight hours a week, but the county paid her only a dollar a year plus per diems. Nevertheless, she formulated storm water runoff regulations stricter than the county stormwater ordinance. She sent them to Wal-Mart on February 12, 2004. Two months later in a phone call to Beemon on April 6, 2004, Wal-Mart project manager Allen Oertel acknowledged that the company altered its plan based on information from Beemon that it did not previously know of. As described just above, later it ended the whole project. Beemon later sued the county and collected backpay for all the time she spent on the job. In 2006 Boal led Charlevoix-area activists in the successful national effort to stop the Coast Guard's plan to conductlive fire exercises with lead ammunition in the lakes. In 2007 Boal led local efforts to stop Sovereign Deed from coming to Pellston. Sovereign Deed was an insurance company that gave wealthy policyholders advance warning and protection in times of terrorist attacks. The company dazzled local politicians, who pushed through tax abatement legislation for it. A year later the company collapsed amid exposure of lies about the CEO's military record and involvement in used car fraud. Boal wrote books on Teamster Legal Rights for members in 1978 and 1984, and currently maintains a regularly-updated online book for UAW members at ellisboal.com. Boal testified before the US Department of Labor's Dunlop Commission in Washington in 1994, and later wrote an article on the same subject in the Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy. He argued to preserve the federal law which guarantees independence of unions, then under attack from employers seeking to undermine them through "cooperation" plans. Data show that cooperation plans do little to improve productivity, and much to diminish labor morale. Ultimately the law stood. Since 2002 Boal helped organize several anti-war activities locally, and debated our local Congressman Bart Stupak in guest commentaries on the subject. Boal's cases include:

Weiss v City of Chicago arose out of a protest on the last day of the week-long Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968, against the Vietnam war and the police riot of the day before. At the time he worked as a school teacher and taxi driver. He was one of 13 -- including convention delegates and newspaper columnists -- who the city tried for disorderly conduct for refusing a police/national guard order to disperse a march of 3000 led by comedian/activist Dick Gregory from downtown Chicago toward the convention amphitheatre. The peaceful crowd had come two miles south to 18th and Michigan when authorities gave the order. The crowd paused. Some grew unruly. An hour later arrests started. In all, 90 or 100 were arrested. Police then gassed everyone else, his lawyer and Boal's sister Nina among them. The arrestees listened to Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey's acceptance speech on a portable radio from the police lock-up.

The City's "disorderly conduct" ordinance forbade:

[failing knowingly] to obey a lawful order of dispersal by a person known by him to be a peace officer under circumstances where three or more persons are committing acts of disorderly conduct in the immediate vicinity, which acts are likely to cause substantial harm or serious inconvenience, annoyance or alarm.

The six-week bench trial was his introduction to legal proceedings. Boal was the only defendant to attend every trial day. His picture was in three Chicago newpapers. Newspapers nationally covered the case. All were convicted. The New York Times reported it on page 1. The trial judge's opinion singled out Boal's conduct. Removal of his marshal's armband prior to arrest was evidence, the judge held, that the group presented a "threat of violence" in airing "emotional" grievances.

The Illinois supreme court affirmed, but on different grounds. Discounting the trial judge's finding, it conceded the

lawfulness of the order must be determined as of the time when it was given, when admittedly, the march continued to be peaceful and orderly, and if unlawful at that time it cannot be rendered lawful by the violence which followed,

But the intended march route was densely populated. There had been violence in parts of the city including a "brief scuffle with some Negro youths" involving other marchers in the area hours earlier. The court reasoned that these facts justified finding that the march would have presented a threat had it continued farther.

As to the ordinance itself the Court said it "defines boundaries sufficiently distinct for us to review the reaonableness of the peace officer's on-the-spot decision."

The US Supreme Court denied review; Justice William Douglas wrote separately, saying he would have granted review and reversed on the basis of a previous precedent which held as to the ordinance:

Conduct that annoys some people does not annoy others. . . . As a

result, 'men of common intelligence must necessarily guess at its meaning.'

All this is described in an account Boal wrote of the case his first year in law school, and a write-up by Nina of the activites of convention week. Meyers Industries, in which the federal Labor Board held that the labor laws did not protect non-union truck driver Ken Prill in his discharge. Prill had refused to drive a tagged-out-of-service truck which had just caused an accident on the interstate in Tennessee. Driving it would have been unsafe and illegal. The Labor Board reasoned that Prill had acted courageously but alone, and the labor laws are only to protect workers who act in concert for mutual aid or protection. Boal took the case to the DC court of appeals in 1985 and 1987, and ultimately lost because the Labor Board wanted to use it to set a new precedent. Today, Meyers defines the rights of workers who are victimized for trying to bring about better working conditions. It is the most widely cited precedent on that subject in labor law. Along the way Boal managed to get Prill back to work at Meyers, and later sued it successfully when it defamed Prill. Maceira v Pagán, in which then-Judge Stephen Breyer of the Boston court of appeals reversed a federal judge in Puerto Rico, and ordered a fired dissident Teamster steward reinstated to his post. The opinion was reprinted in full in a 1982 instructional casebook by law professors at Rutgers, Pennsylvania, and New York law schools. In a later opinion Breyer -- who is now on the Supreme Court -- awarded Boal enhanced fees for the excellence of his work, and the likelihood at the beginning of the case that there was little chance of success. In 1994 one Anthony Lapiana sued Clayton Bernier, a member of Millwrights Local 1102 near Detroit. Bernier had attacked the union leadership at a meeting for its ties to Lapiana, saying he was part of organized crime. Lapiana claimed this was defamation. Boal entered an appearance and sent written questions. He asked Lapiana if he was "a member of the Detroit crime family" and "linked in FBI files to organized crime families in Chicago and Detroit." Lapiana refused to answer. The judge dismissed his case. But Bernier's defense had cost him $6000 in fees. Boal counter-sued at the Labor Board. He argued that Bernier's statements were "concerted activity for mutual aid or protection" -- free speech under the labor laws. On the day of trial Lapiana settled and paid 100%. The cases were Automated Benefit Services and Lapiana v Bernier, Macomb County Circuit Case # 94-5664-NO; Automated Benefit Services and Lapiana, NLRB Case # 7-CA-38518. In a case for a young and public-spirited Native American driver near Petoskey in 2005, he and his client tracked down and presented two bystander witnesses. District Court Judge Richard May listened, and found there was no cause for the officer to pull the vehicle over. The case was over, and his bond returned. The defendant's grateful step-father wrote a letter to the editor of the Petoskey newspaper. In Charter Township of Ypsilanti v General Motors, General Motors said it would begin production of the Chevrolet Caprice at its Willow Run plant in Ypsilanti Township located in Washtenaw County. GM said the new car would generate jobs. It asked the township for 12-year 50% personal property tax abatements in 1984 and 1988. Then in 1991 the company announced it was moving the work to Texas. The township and the county sued for breach of promise. After trial the court ordered the company not to move the work. Residents were elated, but GM appealed. Acting both as local counsel and as a community organizer, Boal helped stitch together a coalition of 356 unions, community organizations, and individuals in ten states to file a brief on appeal as friends of the court. Ultimately the case lost. The Michigan court of appeals found GM never really made a promise. The company had only expressed "hopes and expectations." The ruling taught everyone a lesson. It motivated Boal's later participation in This Is Our Town, which kept Wal-Mart out of Charlevoix in 2004 without having to go to court. In 2013 Boal sued Encana Oil & Gas (USA) in Ingham County for an injunction against 13 US-record-setting horizontal frack wells in Kalkaska County. The company projected a total withdrawal of 388 million gallons of water from the aquifer. At $8 million each, the cost of the 13 wells would have summed to over $100 million. The company told the judge plans were "underway" and it had to start "soon after the first of the year." The judge listened, and then stopped them cold, because the DEQ allowed them too close together. The case was ordered into an administrative hearing. The story is here.

Boal has other outside interests. He sings and plays with the Charlevoix Men's Chorus, plays at various open mikes around town, has completed computer programming and networking courses at NCMC, manages websites, runs or skis 40 miles/week, and competes with the Straights Striders xc ski team. In the Michigan Cup race series of 2015-16 he ranked third in the state in his age group. In 2002 and 2004 he travelled with the National Lawyers Guild to the West Bank, and has written on expelled Palestinians' right to return to their homeland and homes.

Boal is active in Michigan's anti-fracking movement, particularly with Ban Michigan Fracking and Committee To Ban Fracking In Michigan.

Boal was married in 1979 and divorced without children in 2004. He married LuAnne Kozma in 2012. He will authorize viewing of medical records by responsible media. His health is excellent.

|